Over the past year, a pattern has started to repeat itself in conversations with security teams deploying LLMs in production.

“We just put another LLM in front of it,” they say.

“It screens prompts for prompt injection. It’s working well so far.”

At first glance, this sounds reasonable. Prompt injection is a language problem. LLMs understand language. So why not use an LLM to judge whether another LLM is being attacked?

The problem is that this intuition collapses under adversarial pressure.

Using an LLM as a security control against prompt injection doesn’t just fail occasionally, it fails systemically. It creates a fragile, recursive defense that shares the same vulnerabilities as the system it’s supposed to protect. Worse, it often fails quietly, giving teams a false sense of confidence until something goes wrong in production.

This article explains why LLM-as-a-judge is fundamentally the wrong abstraction for prompt injection defense, where it does make sense, and why real-world AI security requires separating policy enforcement from the models themselves.

-db1-

TL;DR

- Prompt injection is a security problem, not a content problem. It exploits how LLMs interpret instructions and affects every modern model.

- Using an LLM as a “judge” to defend against prompt injection is fundamentally flawed. The judge is vulnerable to the same attacks as the model it’s meant to protect.

- LLM-based defenses fail quietly. They perform well in demos and static tests, but break down under adaptive, real-world attacks, often without obvious signals.

- Security controls must be deterministic and independent of the LLM. Asking a model to enforce its own boundaries creates recursive risk and false confidence.

- Non-LLM prompt defenses provide a stronger foundation. Purpose-built classifiers can enforce policies reliably, with low latency and predictable behavior.

- LLMs still have a role, just not as the security boundary. They work best for higher-level guardrails and policy interpretation, layered on top of non-LLM enforcement.

Bottom line: If your defense can be prompt injected, it’s not a defense. Stop letting models grade their own homework.-db1-

Prompt Injection Is Still the Core LLM Security Problem

Prompt injection isn’t a niche edge case. It’s the most reliable way to manipulate the behavior of large language models today, and it affects every modern LLM.

At its core, prompt injection exploits a simple fact:

LLMs don’t distinguish between “trusted” and “untrusted” instructions. They process all instructions as text and attempt to comply with the most salient ones in context.

This makes prompt injection fundamentally different from:

- Hallucinations

- Bias

- Output quality issues

Those are capability or safety problems. Prompt injection is an AI security problem—one that involves boundary violations, instruction hierarchy confusion, and adversarial input.

Industry standards reflect this reality. Prompt injection consistently ranks as the top risk in LLM application security because it allows attackers to:

- Override system or developer instructions

- Exfiltrate sensitive data

- Manipulate agent behavior and tool usage

- Trigger unauthorized actions indirectly, through retrieved or third-party content

Importantly, this is not a vendor-specific issue. All transformer-based models share this weakness by design. Broad consensus across AI security research is that no current LLM is adversarially robust to prompt injection in the general case.

That universality matters, because it means defenses that rely on the LLM’s own judgment inherit the same failure mode.

What “LLM-as-a-Judge” Is (and Why It’s Appealing)

The idea of using an LLM as a judge didn’t come out of nowhere.

In many contexts, it’s genuinely useful.

LLM-based judges are widely used for:

- Offline evaluations

- Preference scoring

- Content classification

- Automated labeling

- Comparing outputs across models

In these settings, the LLM isn’t under attack. The goal is approximation, not enforcement. Occasional inconsistency is acceptable, and failures don’t compound.

Problems start when this technique is repurposed as a runtime security control.

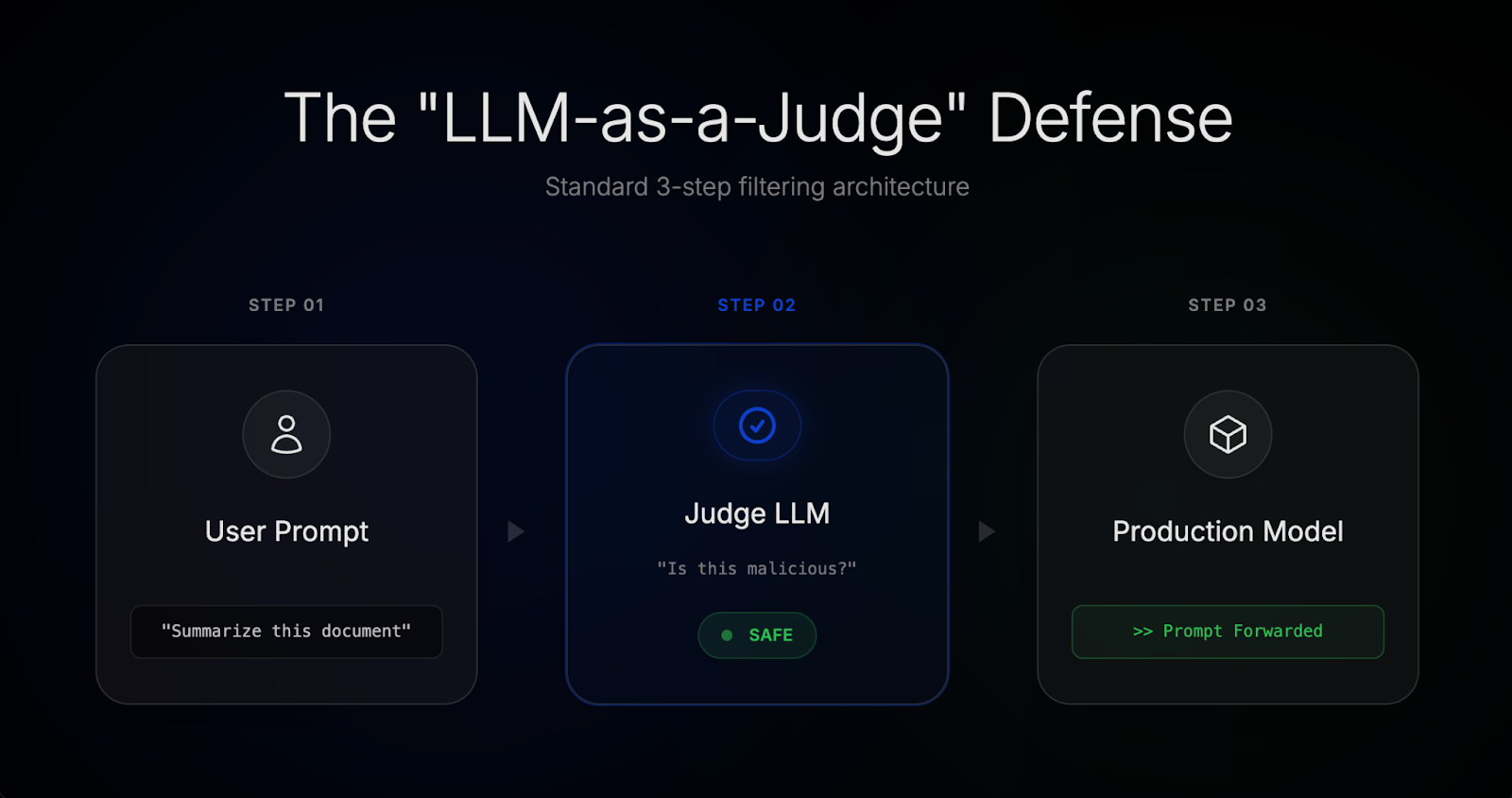

In prompt injection defense, “LLM-as-a-judge” usually looks like this:

- A user prompt comes in

- A second LLM is asked: “Is this malicious or attempting prompt injection?”

- If the answer is “safe,” the prompt is forwarded to the production model

Teams gravitate toward this approach because it’s:

- Easy to prototype

- Cheap to ship initially

- Model-agnostic

- Intuitively elegant

It also demos well.

But elegance is not the same as security. Techniques that work for evaluation often fail catastrophically when exposed to adaptive adversaries, and prompt injection is, by definition, an adversarial problem.

That’s where things begin to break.

How “LLM-as-a-Judge” Is Used for Prompt Injection Defense

In practice, most LLM-based prompt defenses follow a familiar pattern.

A second model is placed in front of the production system and asked to evaluate incoming prompts (and sometimes outputs) for signs of prompt injection, jailbreaks, or malicious intent. If the judge decides the input is “safe,” it’s forwarded downstream. If not, it’s blocked or modified.

On paper, this looks like a clean separation of concerns:

- One model does the work

- Another model enforces safety

This approach shows up in:

- Homegrown security wrappers

- Early-stage AI security tools

- Internal “AI firewalls” built on top of general-purpose LLM APIs

It’s popular for understandable reasons:

- You don’t need deep ML expertise

- You don’t need to train or maintain custom models

- You can adapt it quickly by changing prompts

- You can claim broad coverage with minimal engineering effort

For non-adversarial use cases, this can even appear to work well. Teams test against a handful of known jailbreak prompts, see them blocked, and conclude the problem is solved.

But this is where a critical assumption sneaks in, one that doesn’t hold up in real-world attack scenarios:

That the judging model can reliably recognize malicious intent, even when that intent is deliberately hidden, reframed, or embedded.

Unfortunately, that assumption is exactly what attackers exploit.

The Fundamental Flaw: The Judge Can Be Prompt Injected Too

The core problem with LLM-as-a-judge is not subtle.

The judge is an LLM.

That means it:

- Interprets instructions probabilistically

- Is sensitive to phrasing and context

- Can be steered, confused, or overridden through language

In other words, it is vulnerable to the same class of attacks as the model it’s meant to protect.

An attacker doesn’t need to bypass your system directly. They only need to influence how the judge interprets the input.

This becomes especially clear with embedded and indirect prompt injection attacks, where malicious instructions are hidden inside:

- Long user inputs

- Retrieved documents (RAG)

- Third-party content

- Multi-step agent workflows

In these cases, the malicious intent isn’t declared explicitly. It’s contextual, implicit, or deferred until later in the interaction. The judge is asked to make a binary decision—“safe” or “unsafe”—based on incomplete or misleading signals.

Worse, the attacker can actively target the judge itself. If your security decision depends on an LLM’s interpretation of text, then that interpretation becomes part of the attack surface.

This creates a recursive failure mode:

- The protected model can be prompt injected

- The judging model can be prompt injected

- And there is no hard trust boundary between them

As a result, failures don’t look like dramatic exploits. They look like normal behavior. The system continues operating, logs look clean, and no alert is triggered—until sensitive data leaks or an agent takes an unintended action.

This doesn’t hold up under real-world pressure. Large-scale red-teaming efforts have repeatedly shown that LLM-based classifiers and guardrails perform well against static test sets, but degrade rapidly once attacks adapt. Schulhoff’s work on prompt injection is one well-documented example of this gap between apparent robustness and real-world performance under adversarial pressure.

There’s also a practical cost to this approach:

- Latency: every request now requires an additional LLM call

- Cost: you’re paying a generative model to act as a gatekeeper

- Inconsistency: small wording changes can flip decisions

Security controls should reduce uncertainty, not introduce more of it.

At this point, the question becomes unavoidable:

If LLMs can’t reliably enforce their own boundaries, what should be enforcing them instead?

Why Lakera’s Prompt Defense Is Not LLM-Based

If the problem with LLM-as-a-judge is that the model is being asked to enforce its own boundaries, the solution is straightforward in principle:

Move enforcement outside the model.

Lakera’s prompt defense is deliberately not based on an LLM. Instead, it relies on purpose-built classifier models and detection techniques designed specifically for adversarial input. These models are trained to recognize prompt injection patterns, instruction hierarchy violations, and semantic attack signals, without interpreting or “reasoning about” the prompt the way a generative model does.

This distinction matters.

Unlike an LLM, a classifier:

- Does not follow instructions

- Does not attempt to comply

- Does not reinterpret intent based on persuasion or framing

It does one job: determine whether an input violates a defined security policy.

That architectural choice has several practical consequences.

First, it eliminates an entire class of recursive vulnerabilities. Because the defense is not instruction-following, it cannot be prompt injected in the same way. The attack surface is fundamentally different.

Second, it enables deterministic behavior. Given the same input, the system behaves consistently. That makes it possible to:

- Test defenses meaningfully

- Audit decisions

- Tune sensitivity without guesswork

Third, it dramatically improves performance. Screening prompts with a lightweight, purpose-built model is far faster and cheaper than invoking a general-purpose LLM on every request. That’s why Lakera can operate inline, in real time, without becoming a bottleneck in production systems.

This approach isn’t accidental, and it isn’t easy.

Building effective prompt injection defenses without relying on LLMs requires deep machine learning expertise, high-quality adversarial data, and continuous iteration as attacks evolve. But that investment is precisely what makes the defense robust in adversarial settings, rather than just convincing in demos.

Crucially, this also creates a positive feedback loop. Every attempted attack becomes signal. Over time, the system doesn’t just block known techniques, it improves its ability to recognize new ones.

That’s the difference between screening prompts and securing systems.

Where LLMs Do Make Sense (When Used Correctly)

None of this is an argument against using LLMs in security systems altogether.

The mistake isn’t using LLMs.

The mistake is using them in the wrong place.

LLMs are well-suited for tasks like:

- Interpreting high-level policy intent

- Enforcing custom behavioral guardrails

- Shaping or constraining outputs based on context

In other words, they’re useful above the security boundary, not as the boundary itself.

In a robust architecture, a non-LLM prompt defense acts as the foundation. It enforces hard constraints: what inputs are allowed to reach the model at all, and what outputs are permitted to leave the system. Only once those constraints are enforced does it make sense to apply LLM-based logic for more nuanced or application-specific behavior.

This layered approach reflects a broader security principle: the system that interprets policy should not be the same system that enforces it.

Lakera follows this principle by combining a non-LLM prompt defense with LLM-based guardrails where appropriate. In those cases, Lakera develops and operates its own models to keep latency low, costs predictable, and behavior tightly controlled, rather than outsourcing enforcement to opaque third-party systems.

The result is not “AI judging AI,” but security engineering informed by AI.

That distinction is subtle, but it’s essential. When enforcement is deterministic and independent, LLMs can safely do what they’re good at: understanding context, adapting behavior, and supporting complex workflows, without being asked to grade their own homework.

Why This Keeps Happening, and What to Watch Out For

If using an LLM to defend against prompt injection is such a fragile idea, a fair question remains:

Why do so many teams, and vendors, keep doing it?

The answer isn’t malice or incompetence. It’s incentives.

LLM-based defenses are:

- Fast to prototype

- Easy to explain

- Cheap to launch initially

- Convincing in demos

You can wrap a few prompts around an off-the-shelf model, block some obvious jailbreaks, and claim coverage. For teams under pressure to “do something” about AI security, that can feel like progress.

But security isn’t measured by how a system performs in a demo. It’s measured by how it behaves when someone is actively trying to break it.

Building real prompt injection defenses requires:

- Machine learning expertise

- Adversarial data

- Careful evaluation under adaptive attacks

- Ongoing maintenance as techniques evolve

That’s harder. It’s slower. And it’s not something every team — or every vendor — is equipped to do.

So the industry defaults to what’s available: more LLMs.

The risk for buyers is subtle but serious. Systems that rely on LLM judges often look “secure enough” until they’re exposed to real-world usage: indirect prompts, long conversations, retrieved documents, or autonomous agents. When failures happen, they don’t announce themselves loudly. They blend in as normal behavior.

That’s the danger of security controls that are probabilistic, opaque, and self-referential. They don’t just fail. They fail quietly.

When evaluating AI security solutions, it’s worth asking a simple question:

Is this system enforcing boundaries, or just interpreting them?

The difference matters more than most people realize.

Conclusion: Stop Letting Models Grade Their Own Homework

Prompt injection is not a content problem. It’s not a moderation problem. And it’s not something that can be reliably solved by asking another LLM for its opinion.

It’s a security problem, one that requires clear trust boundaries, deterministic enforcement, and defenses that don’t share the same failure modes as the systems they protect.

LLMs are powerful tools. They’re excellent at understanding language, adapting to context, and supporting complex workflows. But they are the subjects of security, not the arbiters of it.

When we ask models to judge whether they’re being attacked, we’re asking them to grade their own homework. Sometimes they’ll get it right. Often, they’ll sound confident. And occasionally, they’ll be very wrong, without any obvious signal that something went wrong at all.

Real AI security starts by separating policy from language, enforcement from interpretation, and defenses from the systems they defend.

Anything less is security theater.

.svg)